The year is 1983. An airplane crashes in the Alps carrying a deadly virus stolen from an East German lab. The resulting outbreak wipes out nearly all of mankind, save for a few hundred male and a handful of female survivors stationed in several international research outposts in Antarctica. Politicians and scientists in Washington fail to produce a vaccine, and weapons-crazed military advisors – fearing that the Soviet Union is behind the outbreak – initiate an automated self-defense program that will launch a nuclear missile attack if triggered.

As the months pass, the cosmopolitan crew considers the uncomfortable proposition that they will need to re-propagate the human race with limited resources. But such plans are put on hold when seismologist Yoshizumi (Masao Kusakari) discovers that a massive earthquake will strike the Eastern US seaboard, setting off the self-defense system and instigating a nuclear apocalypse.

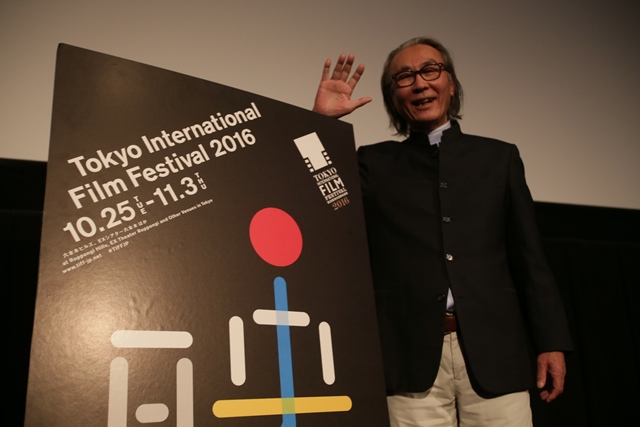

In a lively Q&A session following the screening of a newly restored 4K print of Kinji Fukasaku’s apocalyptic VIRUS on October 28, the film’s cinematographer, Daisaku Kimura, regaled the audience with tales of what the crew faced in hazardous situations befitting the shoot of a disaster movie. Refusing to use a microphone, Kimura yelled, by way of explanation, “ I talk with my gut and from the heart.”

The film was shot on location in Antarctica and other frigid areas and released in 1980, three years before Koreyoshi Kurahara made headlines filming on location for his film Antarctica. “People say [Koreyoshi’s film] was the first major feature film made in Antarctica,” Kimura said, cheekily. “But that’s not true. Our film was the first.”

The film’s well-regarded international cast included George Kennedy, Bo Svenson, and even Sonny Chiba (in a role that is more visible in the restored version’s original 156-minute running time). Kimura, who supervised the restoration, had especially kind words for Argentinian Olivia Hussey, who played the Norwegian love interest to seismologist Yoshizumi in the film. Noting that she had a good camaraderie with the Japanese staff, he said: “Like us, she was an outsider to the Hollywood big shots.” Kimura revealed that the role was originally intended for a different actress who was replaced after Fukasaku had a problem with the way she ran. “She ran like a little girl,” he said, laughing. “This simply wouldn’t work, especially in the last scene. But Hussey ran fine, so we went with her.”

Production company KADOKAWA spared no expense in the film’s budget, the most expensive in Japanese history at the time, allowing Fukasaku to convey the epic scope of Sakyo Komatsu’s sci-fi novel, on which the film was based. “We wouldn’t be able to make a film in Japan like this today, but if we did, it would probably cost something like five billion yen [$50 million],” said Kimura, adding, “KADOKAWA spent 50 million yen alone on location scouting for six of us.”

The production values are evident throughout, especially in majestic shots of the snowscapes of Antarctica, Alaska and Canada, many of which were filmed aerially from army helicopters. Kimura shot many of these sequences himself: “I held the camera on my shoulder, but the wind was so strong my body was swaying while I was shooting.” Particularly difficult was timing the shots precisely when submarines emerged from the sea. “It was all gut feeling and intuition,” he said. “We didn’t know exactly where the subs would surface, so we were flying so low that we were almost hitting the rim of the vessels when they came up.”

Several sequences toward the end of the film required special equipment, including cameras with 1000 mm lenses used for a particularly striking shot of Yoshizumi framed against the background of a humongous, bright orange sun in Peru. “Even if I wanted to take a shot like that today,” Kimura said, “I wouldn’t be able to.”

The film crew was beset by many harrowing challenges, including a well-publicized shipwreck on a Swedish ship while the production unit was being transported to a shooting location in Antarctica. Forced to send out an SOS, the crew was luckily picked up by a small Chilean vessel, but only had enough room for the crew. As Shimura tells it, “The captain told us we couldn’t bring our footage and equipment onboard, but I gathered the staff and ordered them to tie the reels to their heads when they boarded the ship. I told them, even if you die, the film must survive!”

The legendary TOHO cinematographer – who began his career as an assistant under Akira Kurosawa and was 39 years old at the time he shot VIRUS – was also asked what it was like working with Kinji Fukasaku. “We were always fighting,” he laughed. “He was a director who loved control, and I insisted he let me control the shots.” But, he added defiantly, “I ended up placing the camera on top of stacked boxes so he couldn’t look over my shoulder.” The two wouldn’t work on another film together for six years after VIRUS, but in the end, Kimura had kind words for the Toei stalwart: “We were only able to make this film because of Fukasaku.”

Kimura was energetic throughout the Q&A session, leaving the interview chair at the end to walk out to the audience and deliver his final words: “People call me crazy, but I’m just film crazy. I’m also 77 years old!” He declared that he’s not done with filmmaking yet. “Keep your eyes out for an announcement, because I plan on doing something next year. But if you don’t hear anything, then forget what I just said, since my project probably got cancelled.”