“Snow Woman (Yuki Onna)” was one of the legends that Irish writer Lafcadio Hearn recounted in his 19th-century omnibus of Japanese ghost stories, “Kwaidan.” The classic has been retold a number of times in Japan in various media, most famously as a movie by Masaki Kobayashi.

TIFF habitué Kiki Sugino has now created her own interpretation, which received its world premiere on October 28 in the main Competition. A purposely timeless retelling that foregrounds the tale’s sexual subtext, the director-star has also shifted the story’s focus to desire, rather than fear.

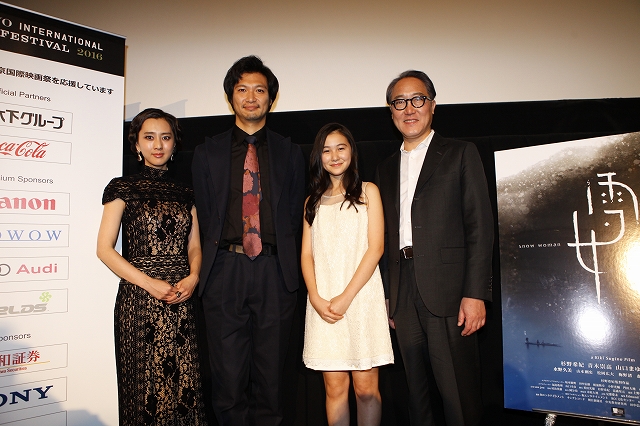

At a press conference following the screening, the ambiguous character of the film was commented upon by the youngest member of the cast, Mayu Yamaguchi, who plays the daughter of the union between a ghost and a human. “I thought it was beautiful,” she said, “but I didn’t completely understand it.”

Sugino explained that she reread the story three years ago and “wondered how it could be applied to our modern world.” Her reimagining follows Hearn’s metaphorical purposes faithfully, but adds extremely subtle modern touches. In the opening scenes, in fact, the movie seems to be set in the past. A hunter, Minokichi (Munetaka Aoki), and his older friend, Mosaku (Shiro Sano), are trapped in a blizzard while tramping through the mountains and take shelter in a broken-down old cabin. Minokichi awakens to find a spirit (Sugino) hovering over Mosaku, seeming to suck the very life from him. The spirit warns Minokichi that if he ever tells anyone about her, he will also die.

Filmed in evocative black and white, the scene is fantastical, so much like a dream that Minokichi himself doesn’t seem to believe it — even when he awakens and finds that his friend is dead. But he says nothing to anyone. Some time later, Minokichi meets and marries a woman from outside his village named Yuki (also played by Sugino), which means “snow.” They have a child they name Ume (Yamaguchi), but when people in the village start dying mysteriously, the villagers point fingers at the outsider. Minokichi’s boss, Eisaku (also played by Sano, in another doubling), who is the nephew of Mosaku, goes so far as to accuse Yuki of murder. But he does not say this to her face.

The movie’s most modern touch is its depiction of the physical attraction that makes Minokichi’s and Yuki’s relationship understandable, despite Yuki’s resemblance to the spirit in the snowy hut. During the press conference, Aoki pointed out that he was moved by “the traditional atmosphere” of the script. The movie was shot in the mountains of Hiroshima Prefecture and the city of Onomichi, which is famous for its rustic architecture and hilly terrain.

One foreign journalist asked Sugino what she wanted to bring to the story that audiences had not seen before. When she read it, replied the director, “I had lots of questions.” She reread it, and decided to explore the uncomfortable idea that a non-human and a human would make love and produce a child, whose form “is not clear” in the story as Hearn wrote it. She wanted to investigate how that child navigated a situation where her provenance was undetermined.

Sugino also explained, “I wanted Minokichi to suffer through difficulties” in determining whether or not his wife was responsible for the death of a good friend, and in the end he would wonder if his love was greater than his resentment. The fact that sex has something to do with this determination is perhaps the film’s most powerful theme.

With regards to casting, Sugino said she expressly wanted Sano, the most well-known actor in the film, to appear because he is a great fan of Hearn’s work and has even performed dramatic readings of the author’s writings overseas.

Several journalists expressed interest in Sugino’s ability to juggle the dual demands of acting and directing. Aoki mentioned that he was amazed at the director’s ability to suddenly break character in the middle of a particularly emotional scene, so that she could rush to the monitor to make adjustments. When asked about the film’s unique use of lighting, Sugino explained that she wanted Yuki to be going into or coming out of a dark place as a way to develop her character. After all, Yuki essentially appears from nowhere, and one of the subtexts of the story is fear of the “other.” The villagers’ mistrust of the young woman has less to do with their fears that she might be a demon, and more to do with the fact that she is an outsider — emphasizing a theme that guides so much of our discussion in today’s world.

One reporter commented that it was auspicious that Snow Woman was making its debut a few days before Halloween. Responding to his question about his favorite “monster,” Sano said that he has always been intrigued by the “Buddhist priest who went to funerals to eat the dead.” The journalists laughed, although the remark surely raised goosebumps.