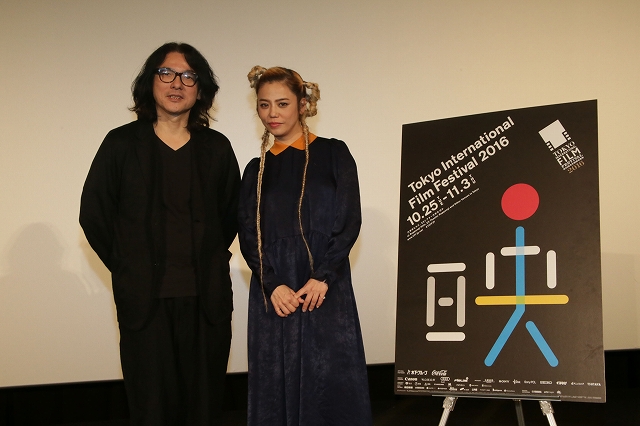

Proving to be one of TIFF’s biggest draws, Shunji Iwai again took to the stage on October 28, this time with his Swallowtail Butterfly star, Chara, and was greeted by prolonged applause. The audience had just experienced all 148 minutes of his 1996 masterwork, yet they clearly welcomed the chance to sit for a while longer, eager to hear the film’s creator and its muse reminisce.

Arriving just one year after Iwai’s Love Letter had taken Asia by storm in 1995, Swallowtail Butterfly demonstrated the budding auteur’s extraordinary versatility — and prescience — as well as blazing a unique new template for the interplay of visuals and music in film.

Shortly before Swallowtail’s release, Iwai’s Picnic (also 1996) won him a second consecutive award in the Forum section of the Berlin Film Festival, bringing him to even greater international attention. The trifecta of Love Letter, Picnic and Swallowtail Butterfly marked him as a force to be reckoned with — as important to Japanese filmmaking as Quentin Tarantino and Pulp Fiction (94) had been to America’s. But it was too soon to understand just how prophetic his third film would prove to be.

The world of Swallowtail may never actually exist, but the struggles of its immigrant protagonists seem so real, their emotions so authentic, that it’s easy to imagine there are people like these in every urban center of Japan, scratching out a living, struggling against prejudice, dreaming of one day returning to their homelands.

In the near future of the film, the yen is the strongest currency in the world and Japan has attracted millions of foreign inhabitants. Many of them live in the Yen Town ghetto outside Tokyo and work on the margins, always hustling, sometimes committing petty crimes. Speaking in a mélange of Japanese, English, Mandarin and Cantonese, these outsiders often have no choice but to band together, to create new “families” to help and support each other.

In one such family, Chinese immigrant Glico (Chara) and her boyfriend Fei Hong (Hiroshi Mikami) find a clever way to make their dreams come true, and are soon able to afford their own nightclub. En route to becoming Yen Town’s first crossover pop star, however, Chara is led to betraying Fei Hong, who winds up jailed and then beaten to death.

The film’s propulsive, sexy, poignant vision of a multicultural, multilingual future still feels as smart today about identity, ethnicity and family as it did 20 years ago. Iwai recalled, “I was watching all these shows about outcasts, like the American TV show “The Beverley Hillbillies,” and Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America and Coppola’s The Godfather were my favorite films. I wondered how I could write something [with similar themes].

“I wanted to depict the immigrants as human beings,” he continued. “I was told that I made their lives seem too happy, but I admired their underlying strength more than I did that of the Japanese, who seemed to have lost theirs.”

Iwai and Chara both struggled to remember exactly when and how they’d met (through mutual musician friends, probably in the early 90s), but then recalled that the director had asked the singer to appear in both Picnic and Swallowtail. Said Iwai: “I was a fan of Chara’s from her debut as a singer. I was listening to her “Violet Blue” while writing the script for Swallowtail Butterfly. So I remember the very early script when I hear the music, even now.”

“I remember you asked me to act, but I got pregnant,” said Chara, “and I was waiting for the release. [much laughter] I’d never been in a film before, and shooting Picnic, it was so hot!” Iwai concurred: “We thought we would die from the heat.”

Japan Now Programming Advisor Ando Kohei lauded Chara’s linguistic abilities in Swallowtail, and was surprised to learn that “We all started from zero. I took Chinese lessons for about 2 months, and it was a real struggle. But gradually, it became like music to me.”

Iwai remembered, “Hiroshi Mikami’s Chinese also sounded like he was a native. Sometimes I needed the actors to ad lib, and I would ask them to say something. They would look at me and ask ‘Which language?’ I totally forgot they were not native Chinese. “

The film’s phonological chaos is heightened by a subset of non-Japanese who are now more prominently in the spotlight, represented by the hilarious Caucasian man who calls himself a “Third Culture Kid.” Although he grew up in Japan and can speak only Japanese, he is always mistaken for — and treated like — a foreigner.

“We shot a lot of singing scenes,” said Chara, “but I was really surprised when I saw the film, and it had so much music! My favorite scene was when we find the piano in the garbage and we put it on the truck. That’s really why I took the role. But nothing was written about which song we should sing as the truck drives away. I love ‘Break These Chains,’ so that’s what we wound up singing.”

For Chara, who returned to her flourishing career in music after the two starring roles in Iwai’s films, “Swallowtail was a great experience and I loved making it. My life changed completely. It was the starting point of many stories for us.” Japan’s master storyteller nodded agreement. “I was so happy to work together,” he said.

For those in the audience who had just watched Swallowtail Butterfly for the first time or for the 10th, there seemed to be a collective understanding that its impact would endure. The director’s fans around the world know this: Once you watch a Shunji Iwai film, no matter who you are, no matter where you’re watching from, you will never, ever forget how it made you feel.