An ordinary nuclear family moves to a house in suburban Tokyo, equipped with the latest in high-tech security systems. The father declares that he wants to protect his family from a society in which dangerous things are happening outside. Looking uneasy, his daughter asks, “What if the danger comes from inside?”

Six years after his last film, Wandering Home (10) opened the Japanese Eyes section at the 23rd TIFF, 81-year-old maestro Yoichi Higashi returns to TIFF with his creeping drama Somebody’s Xylophone, and proves he still has plenty of what it takes. Higashi’s filmography includes masterpieces like Third Base (78) and No More Easy Life (79), and several films about the complex psychology of the Japanese housewife.

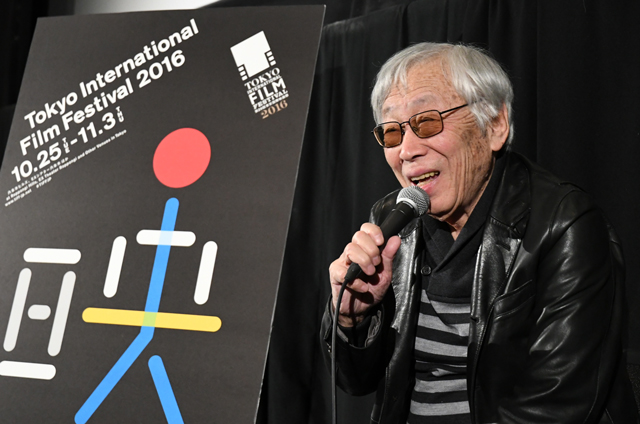

Higashi seemed very energetic when he ascended the stage with programing adviser Kohei Ando after the Japan Now screening on October 30. Since the film allows viewers to interpret it in diverse ways, Ando joked, “This film makes everyone’s xylophone sound in some way.”

The project’s inception was an accidental encounter at a bookshop: “I’d read the original book [on which the film is based],” explained the director, “and I felt it was something that I must direct, not others, because they would ruin it. This is very arrogant, but that’s honestly how I felt.”

Somebody’s Xylophone concerns a lonely woman who begins stalking her hairdresser, and seems to be shot to purposely resemble a TV melodrama for bored housewives. But Higashi is actually parodying these soap operas; instead, his film begins to peel back layers of casually obsessive madness. The xylophone of the title is a musical link connecting an early, happy memory from childhood with her present isolated state.

As opera music plays gently in the background, the camera slowly moves in on married woman Sayoko (Takako Tokiwa), indulging herself with a glass of red wine in broad daylight; a thirty-to-forty-something who has lost none of her youthful beauty, she does not appear to be as urbane as she imagines. She is thinking about Kaito (Sosuke Ikematsu), a charming hairdresser in Sayoko’s new neighborhood, a fashionable guy who is forever wearing scarves and hats inside the salon.

After the usual practice of hairdressing, Kaito asks for Sayoko’s e-mail address so the shop can send promotional announcements. However, by the time their online exchange becomes casual enough for Kaito to send a picture of scissors, calling them his ‘fighter’s soul,’ Sayoko’s obsessive nature can no longer be hidden. Behind the backs of milquetoast husband Kotaro (Masanobu Katsumura) and her worried daughter, Sayoko not only visits the beauty parlor constantly, but also finds out where Kaito resides. Xylophone is a suspenseful drama and a dispassionate romance, with the housewife’s preoccupation soon threatening to destroy the equilibrium of several households.

Ando lauded the leading lady’s performance. “It’s Takako Tokiwa’s best film,” he claimed, “Her acting was restrained and non-emotional. Every time I watch this film, I interpret her facial expressions in different ways. Was that your intention?” Higashi admitted, “When I first met her, she told me, ‘I’ve watched many of your films, but I didn’t realize you are still alive,’” laughed the filmmaker. “I told her, ‘Please don’t bother trying to develop your character.’ She seemed flabbergasted and said, ‘This is the first time that a director told me that.”

According to Higashi, acting is not structuring a fictional being and presenting it to spectators. “When I watched this film tens and hundreds of times during the editing process, I understood Ms. Tokiwa’s acting differently. Which means that film reacts to the spectator’s state of mind. Generally, it’s called restrained acting, but for me that is exactly what acting is.”

It seems, however, that the veteran director expects more: “Fortunately, both Ms. Tokiwa and Sosuke Ikematsu are not just great actors, but talented at analyzing their own films objectively. One day, Ms. Tokiwa told me, ‘You are trying to depict the reality that surrounds all of us today in society. Despite focusing on one woman and a man, you are actually trying to show the whole situation.’”

“Some people might feel this is just a personal love story,” continued Higashi, “But nothing like that happens in a vacuum. There are always political or social influence on all individuals who live in society. On the other hand, even if film appears to be very political or social in its theme, it’s also supported by individuals. You cannot separate individuals from society and politics.”

One audience member commented that she was interested in the ambiguity of the distinction between reality and imagination in the film. Higuchi joked, “Actually, I have trouble distinguishing what is reality and what is not. Somewhere in my mind, I’m not sure whether the fact that I’m here is a dream or not.” Even on a Sunday morning, the audience was clearly excited to see the legendary filmmaker’s latest work, about a protagonist with an unrelenting obsession, and director himself — and they knew his presence was not a dream.