Lav Diaz is a master of very long films. His current opus, A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery, a sprawling epic covering a particular period in the history of the Philippines, clocks in at 8 hours. It’s a bit of an anomaly for standard contemporary film, not only for its length, but for its beautiful retro feel. Shot in gorgeous black and white, and framed in an old-fashioned aspect ratio, the artistic choices make perfect sense, complementing the many themes and ideas, and Diaz’s passionate feeling for and sense of Filipino history.

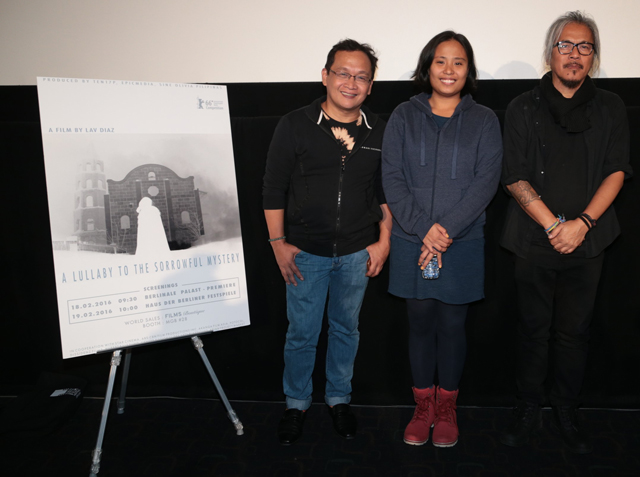

The Filipino director appeared after the October 31 screening of the film in TIFF’s World Focus section, along with two of his stars, Hazel Orencio and Joel Saracho. The film won the coveted Silver Bear Award at the Berlin Film Festival in September.

Diaz opened up the Q&A session by admitting, “I have jet lag. I just got off the plane 3 hours ago.”

Saracho, perhaps concerned about the audience’s potential jet lag, added, “Congratulations for surviving 8 hours.”

Diaz had just flown in from Boston, where he now has a fellowship at Harvard. He described it as “just hanging out there, trying to find my way in this overwhelming academic culture there at Harvard.”

He added, “They give you space and time to work on some projects and programs. So, I’m programming Filipino cinema from the 1970s epoch. If you check the year 1976, there’s like a peak in Philippine cinema. Most of the works from that year are masterpiece from Lino Brocka, Mike De Leon, Mario O’Hara — they’re all masters.”

He described what he was trying to accomplish with Lullaby: “The film is very particular about a period. This is the Philippine revolution, the years 1896 to 1897. It’s a critique and examination of that period of history, the nature of that evolution. Not just the spectacle that happened. It’s more of an examination and a confrontation of that part of our history. So you don’t see the battles. You see real characters, living during the period.”

He continued, “We integrated the very works and personas that inspired that revolution — like the works of Dr. Jose Rizal, the novels “Noli Me Tángere” and “El Filibusterismo.” We borrowed parts of those novels, the characters and symbols. And another thread of the film is the Filipino mythology. So these three threads, they work together. They are integrated. It’s the whole gamut of that period.”

Diaz is fierce about where his cinema comes from. He explained, “First of all, the inspiration of my works, is the Filipino struggle. It’s our story. And I think any culture can relate to our struggle also. It’s more of adapting the stories that I’m familiar with.”

He’s also fierce about his aesthetic choices, but aware of the limitations of having an audience for his films.

“You can see,” he said, “it’s not being shown in so many places, only in festivals because of the length and the kind of framework that we’re doing. With this kind of mise en scene, they’re always putting us in the ‘alternative cinema’ sections, because of the length. That’s why it’s very imperative to have this kind of space at festivals.”

He added, with a laugh, “Oh yes, it was commercially release, but it bombed. Nobody went to the film. If anything, we have the 2 most popular actors there, but because it’s 8 hours only a small percentage of the country went to see the film.”

“But we’re not complaining. It’s part of the struggle, the propagation of this so-called ‘serious cinema,’ There’s no easy fix. You cannot rush it. You have to give it and just let it grow. Culture grows that way.”

“Cinema can wait,” he added with a sly smile.

Diaz continued, “If you create cinema that is not part of the convention, you must have an awareness that the audience is not there. You have to develop that kind of audience.”

When queried about how long it took to shoot his latest film, he surprised the audience, responding, “We shot the film in 22 days only. But the preparation was 17 years. I started the script in 1999.”

Saracho described the process of making the film from an actor’s point of view: “We woke up every day, not knowing what scene would be shot. Because the process is: Lav wakes up at 3:00 in the morning and plays his guitar, then writes and at 8:00 the actors are handed the script for the day.”

“Each scene would be about three pages long, which would be shot in one day. So really have to have that skill to memorize and do whatever he wants you to do. And it’s driving the actors crazy, most of the time.”

“But basically, at 6:00 in the evening we’ll start drinking anyway, so it’s fine.”

He added, “Seriously it was a very creative, very serious process, especially for us actors. Everything was shot in one long day. And you have very little room to commit mistakes, because otherwise you have to do everything from the top, all over again.”

The session ended with a lively discussion of film and culture in the Philippines, during which Diaz passionately reiterated that film and culture must be grown and nurtured and that it would take time, perhaps longer than the length of any of his movies. And he said once more, “Cinema can wait.”